- Home

- Greg James

Lost Is The Night Page 8

Lost Is The Night Read online

Page 8

The swine-daemon’s sack-like stomach heaved in and out as it crashed towards the swordsman. She watched him stare at the monstrosity before him, and she wondered if he feared for his life.

The beast swung one of its tuberous arms.

The swordsman turned on his heel, pivoting, moving as water moves, passing through the air as light falls, and two swollen fingers from the creature’s bulbous paw thudded to the ground. A steaming ichor bled from the wounds, making Cacea choke and her eyes water.

The beast shrieked, enraged. It swung its other arm at the insect-thin man that had dared to wound it. The swordsman danced away, faster and swifter than a dead man should be able to, as another limb slammed into the ground where he had stood. He carved reeking flesh from the arm and the swine-daemon reeled away in pain.

Cacea held her breath. The odour from the thing and the wounds being opened in its rancid body was worse than a refuse pit.

The swine-daemon snarled and slung its jaws wide as it charged the swordsman.

What happened next seemed to take place in a dreadful slow motion. As Cacea watched the beast’s drooling snout reach towards the swordsman, he moved back and then forwards. He was in the air, planting a heel hard on the snout, making the monster snort as it was driven into the dirt, and then whipping his blade around, he drove it down, hard and fast, through the swine’s bulging skull.

The creature screamed and reared back onto its legs, flailing its wounded arms, almost ripping the sword from its wielder. But the swordsman spun away through the air, withdrawing his weapon from the grievous wound it had made. He danced out of its reach as it struck about, and stamped along the water’s edge, half-blind, enraged, and unable to find its quarry. The creature continued to cry and call despite the gaping hole in its head.

It should be dead, she thought, but still it walks.

She felt a coldness wash over her as the swine-daemon turned and crashed away, back towards the heart of the lake, where the waters rose and covered it over. It had given up the fight. Soon, there was quiet again in the cavernous depths.

The swordsman returned to her side. Before sheathing the blade, he gave it a shake and Cacea watched the daemon’s blood evaporate from the metal as vapour.

“You are most fortunate I was here beside the lake when you came to this place.”

She struggled to find words. “What was that thing? ... Who are you?” she eventually asked.

“That was a Chalga; a loathsome thing. As for myself, in my short lifetime I was known as Anhe, the twenty-eighth Prince born to the line of Gaen’yhe, and heir to the Crown of Ain’Soph. But they have called me Anhedon the Last for many years longer than those I spent alive.”

“How came you here? What is this place?”

“I have been here longer than I ever imagined … and if you do not know of me then my history is no more spoken of by men.” Anhedon gestured at the space around them. “This has been my home for a thousand years or so, perhaps many more than that. I do not know for true. Time does not pass here as it does in the world I once lived in.”

“Yes, but where am I? I’ve never seen anything like that ... that thing in the water.”

“You would not have done. You are in the Thoughtless Dark.”

Despite everything, Cacea laughed. “You jest. Only the dead can go there.”

Anhedon’s eyes were steady and serious. There was no trace of humour in them.

Cacea paled and stepped away from him once again. “No. No. I cannot be dead. I am here. I am alive. I breathe. I can feel my heart’s beat.”

A thin smile unpeeled Anhedon’s lips from his grey teeth. “I know not if you are dead or alive, Cacea. The laws of the world do not matter here. The Thoughtless Dark is oblivion, void, and nightmare-space. And this place is not of the Dark wholly, it is merely a piece of a dead world drifting along on its dark currents.”

Cacea looked at the ground beneath her feet. “A piece of a world?”

Anhedon nodded. “Even so. There are more worlds in the heavens than you could possibly imagine, though knowledge of them has all but vanished from the learning of men. We are outside the world as you know it. Remember that, for you will see much that is strange here.”

“But you…” she started. “You’re not ... alive. You said my short lifetime ...”

It was Anhedon’s turn to laugh at her words. “I realise I am not so comely to look upon as I once was, but I am not possessed as others you might have seen. My body is wasted, but my mind is my own.”

“And your eyes.”

A sad smile touched his lips briefly. “Yes, and my eyes. They have left those to me, at least.”

“What happened to you, to make you like this?”

“Ah, it has been an age since I was asked to tell my sad story. I bargained with the Gods, more fool me. In the name of vengeance, I offered myself to Voyane as her Blood-Champion. She accepted. I was the last of my line: a learned and wise scion of humanity, that we were. My folk dwelled on an isle far off the shores you know, where we preserved knowledge and sought to learn as much about the world as it was before the white fire. Ain’Soph was its name, and I was raised in Helde Naern, the shining sister-city to Anaerthe Morn.

Anhedon’s voice grew harder and colder. “But ... it burned. From Morrow’s End to the Dreamshores, the land of my fathers was turned to ash and the cities reduced to ruin. I swore vengeance from the bow of my ship, and so I spoke with Voyane. She granted me strength, for I am a natural-born creature of libraries and archives. The battlefield was no place for me as I was then. But, in exchange for strength, she took my soul from me. She holds it still, along with the souls of all my people.”

“Why would she do such a thing?”

“Because the Gods are not good. They are ravenous abominations who seek only to consume, gorging themselves on the fates of the living. They take our words from us and make them into a vile poison that suits their own ends. Voyane took my soul, aye, and her acolytes forged the blade I now bear. She then sent me forth into the world to carry out my vengeance, but what she did not deign to tell me was that my wrath would not be sated.

“Because the one who slaughtered my people could not be slain by sword or spell. He out-manoeuvred me and cast me into this purgatory, where I have dwelt ever since. The souls of my people howl for succour as they wander lost in the void. The wrong word in a prayer and a God’s black will was done. And so, here I am.”

“Who was the one that imprisoned you here?”

“His name was Khale.”

Chapter Fifteen

Khale and Murtagh made their way through Castle Barneth; all the while, Murtagh thought on how the atmosphere of the place had changed. He knew what it felt like when its people were asleep, but it did not feel like that now. The air tasted dead and still. Every footstep sounded like an echo in a chasm. And he was certain that it was colder than it should be, despite the spell of winter having been broken.

Their search for Cacea had been so far fruitless. They had found bodies—of the mortal and the monstrous. Murtagh thought on whether the death of such degenerate creatures was a mercy. Few could be left alive within the walls of the castle by now. Murtagh wondered what dark things would come to pass when the last survivors fell, and whether he would be among them.

Suddenly, the castle shook around them.

The light itself waned, plunging them into darkness.

Murtagh cried out; Khale said and did nothing. From somewhere in the dark, there came a deep roaring, born from no mouth or throat. It was a sound of something greater: a vortex of sound and motion that created strange images and reverberations in the Captain’s senses.

Murtagh saw the blurred outlines of the space around them, but from some other place, a seething flow of cloud forms seemed to pour forth and swim across his vision. He beheld shapes that he took to be pillars, reaching upwards into an aerial ocean of colour and scintillating light. It was as if he were passing through a hushed temple space,

although he was not walking at all.

Before the scene broke apart, the veil sundered and Murtagh saw what he thought, at first, thought to be countless stars receding. They began forming a definite shape as the black spaces between them howled an infinite scream. The shape they took on was the scarred, rutted visage of Khale, and those stars that made up his eyes burned with a dismal yellow brilliance.

As he stood there, transfixed and breathless, Murtagh was sure things he could not see were passing by, their bodies coming into contact with him for but a moment, though long enough for him to ascertain they were colossal beings that saw him as a creature small and of no consequence.

The star-born vision of Khale dissolved into air, and Murtagh found himself both seeing and not seeing. He saw the walls, the floor, and the chambers beyond, as though everything around him was composed of dark, smouldering glass.

Shadowglass, he thought, and a cold feeling passed through his body at the memory of Timoth’s mirrors and the things that had emerged from them.

Other shapes and forms passed over and through his surroundings: luminous surges of chaotic force, and pulsating masses that seemed to writhe and flow with the rhythms of what he could see suffusing everything. They possessed no mouths, yet consumed and passed through one another as if they were not there.

Murtagh felt a dreadful presentiment.

Light returned as suddenly as it had departed, and both men scanned their surroundings.

There was little change, except for something on the walls. Murtagh approached it and tentatively touched the strange substance. It was soft like flesh and grey like evening clouds.

“What is it?”

“Residue. The leavings of certain beings.”

“You saw them, Khale?”

“I felt them,” said the Wanderer. “It is worse to feel them than to only see them.”

“What are they?”

“The Gods in Shadow. They have been disturbed and are wandering abroad.”

“The Gods ... will they come again?”

“I have no doubt of it.”

“Why were we spared?”

Khale looked at Murtagh, a demonic smile crooking his scarred lips. “It is well for you that you walk with one such as I. Let us leave it at that.”

“Hold. Do you hear that? Someone comes.”

“No,” Khale said, “Something.”

Large and stinking of filth, it came lumbering out of the shadows of a passageway ahead. Its likeness was of a gigantic swine on its hind legs, with spittle and grey mucus coating its mouth. It let out a shrill, honking cry.

“What is that?” Murtagh cried.

“Something of the Dark. As a wound opens and festers, so is the way with such a portal into hell. First, the things you might say are smaller come through, but there are always worse things waiting for their time.”

“What should we do?”

Khale had no time to respond.

The swine-daemon charged and caught him full in the chest, lifting him off his feet as it surged on until he was driven into a wall. Murtagh fell back, his sword hanging loose in his hand.

What could a mere man wielding a sword do against a thing composed of such reckless hate?

Khale raised his fists, wound them together, and brought them down as a hammer blow on the base of the swine-daemon’s raw neck. The beast squealed and bucked, loosening its hold for the moment—enough for Khale to wrestle himself free. The creature swung its powerful, heavily veined arms and knocked the wind from his lungs, making him stumble and crash to the ground. It stood over him, grumbling wetly in its throat. Then it reached down, fastened the webbed stubs of its fingers around Khale’s throat, and began to throttle him.

The Wanderer’s face turned scarlet as he twisted and turned, trying to free himself and retrieve his fallen sword, but he could not reach it. His eyes searched for Murtagh. The old man stood aside, uncertain.

He could just stand aside and watch.

But no, he could not.

He had been standing in the shadows for too long. Bartering with coin for the people of Colm had gone ill for him. And if Khale fell, he doubted he could take this monstrosity down alone, let alone survive.

Murtagh cut the swine-daemon across its flank. Foul blood welled from the wound, and the creature turned its head to glare at him. Its eyes were the colour of ripe boils.

It let Khale go and swiped at him. He parried the heavy blow, barely. The steel of his sword caught in the knotty flesh of the creature’s arm, and it howled, showing him the ragged flesh and root-like teeth nestling in its maw.

Khale caught the creature from behind, throwing it off balance. The horror stumbled and crashed into a wall before righting itself.

Murtagh watched as Khale stroked a palm along the length of his blade. The two-handed sword began to smoulder and wreak an amber smoke. The swine lowered its bullish head and charged.

Khale brought the sword down and caught the creature on its crown. The swine-daemon toppled as a tree in the forest is felled, trailing supernatural vapour from its wound.

The Wanderer was upon it. He cast his sword to the ground as he straddled the upper torso of the beast. He clamped his gnarled hands onto its head, working his thumbs into its shrunken eye-sockets and locking his fingers onto the shape of its distorted skull. The creature bellowed and writhed. It shattered stone with the beating of its crooked fists. But Khale did not let it struggle free. Murtagh could hear a black speech being uttered by his tongue. His companion braced himself against the creature and the ground. Muscles tensed, locked and bulged with a strength drawn from other spheres.

The swine-daemon’s bellows changed in timbre, becoming a pained howl.

Murtagh heard the sound of skin, then flesh, then muscle tearing. Blood spattered onto the ground. Khale threw his head back, his face drawn tight into a bestial leer that scarred the air itself.

The creature’s howl became the sound of something drowning. A crack of bone and cartilage was followed by an intense shower of gore and black matter. Finally, there was a great, wet, ripping sound as Khale heaved and tore the beast’s head free from its shoulders. He got to his feet, held it high and shook it so that blood rained down into his hair, staining it dark.

He roared his victory to the reverberating depths of Castle Barneth, before casting the lumpen head aside. Looking down at it, catching his breath from the exertion, Khale sneered one word at it, “Fatality.”

Murtagh probed the torso of the fallen horror with the point of his sword.

“If the way to the Thoughtless Dark is not closed, we shall see more such things,” Khale panted. “They will not stop at rampaging through this castle, or over Barneth’s lands. They will travel south. They will travel to the west and farther north. The last of men will be consumed by them, and this world will fall into the Dark as so many have before.”

“How can we stop it?”

“We cannot entirely,” Khale said, “all worlds succumb to the Thoughtless Dark in time. Have you not seen how there are fewer stars in the sky as the months and years go by, Murtagh?”

“I had not thought much on it.”

Khale snorted. “Of course, you would not. So much has been lost since the white fire. The knowledge of men has been reduced to less than a candle burning alone in the night.”

Murtagh shrugged. “What say you then? We still have not found Cacea.”

“I fear she is not far from whomever has opened the way,” Khale said. “I was not certain before, but we have not yet seen her corpse. I know she is alive, and that she awaits us on the path we are following.”

“How can you be so certain, Khale?”

“Because there are forces at work this night that would see her live as much as I.”

“And who might they be? Or can you still not tell me this?”

“You have heard of the Crone?”

Murtagh’s face whitened. “The Crone of the Peaks, and her Sisters?”

“Th

e same.”

“You serve a fearful power, Khale.”

“Some might say I am one myself,” the Wanderer said, holding up a blood-soaked bundle in one hand.

“What is that?”

“A way to find Cacea and the sorcerer behind this night’s work. A token of flesh and blood from this beast. Bring me fire from a torch.”

Murtagh felt disquiet in his heart as he brought the torch, and Khale set the ragged bundle of flesh and matter on the ground ablaze. Muttering darkly to himself, the Wanderer bent over the roasting carrion as oily ropes of smoke began to rise from it. He hawked and spat into the low flames.

Slowly, the smoke resolved into a rough outline of a wizened face.

Murtagh drew in a tight breath.

“Do you hear me, Crone?”

“I hear thee, Khale. Why do you call upon me?”

“My task goes ill.”

“That is not my concern.”

“You would have those who dwell in the Thoughtless Dark ravage your forest and burn your lands, then?”

“I would not.”

“Then, tell me where I might find the one who has disturbed the Dark and raised its denizens this night?”

“You try me, Khale. There will be a reckoning for this.

“Later. Tell me.”

“In the highest tower that sinks to the lowest place, you will find the one you seek and the one that wears his face.”

The vision flickered and faded away.

“Old man, do you understand her words at all?”

“I think that I do. Follow me, Khale.”

“Where do we go?”

“To a tower that rises high in the lowest place.”

“The dungeons?” asked Khale.

“Aye, to a sanctum beneath them, I believe. He told me of it in passing a few moons past.”

“So you might lead me there, perhaps?”

Murtagh frowned, “How would he know that either of us would live long enough?”

“Because not all is as it seems, Murtagh. Did I not say the dead we fought were too soft? That is where he is hiding, where he is waiting,” Khale said in a low voice, “and where he shall die.”

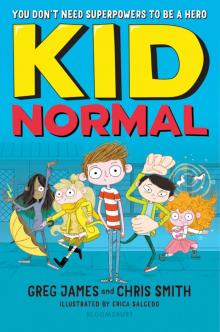

Kid Normal and the Final Five

Kid Normal and the Final Five The Sceptre of Storms

The Sceptre of Storms Made for the Dark

Made for the Dark The Sword of Sighs

The Sword of Sighs This Darkness Mine

This Darkness Mine The Door of Dreams

The Door of Dreams All Things True

All Things True The Stone of Sorrows

The Stone of Sorrows The Oeuvre

The Oeuvre Zombies by Moonlight

Zombies by Moonlight Lost Is The Night

Lost Is The Night Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1)

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One)

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes

Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes Kid Normal

Kid Normal