- Home

- Greg James

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) Page 8

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) Read online

Page 8

The dogs were fighting over the remains of a child.

She did not leave, though. By evening, the dogs passed on. Scavengers never stayed in one place for long; such creatures were cowards, driven to action only by the pain of an empty stomach. She approached the ruined wagon carefully with her sword drawn; every step made as slow and quiet upon the grass as possible. Reaching the wagon, she searched for anything she could use. She found wood enough for a good fire, and black, salted meat packed away with fruits that had not yet turned sour. There was even feed for her horse, which she knew the poor, tired beast would be grateful for. Without some rest and food, she doubted whether her steed would have lasted much longer after the fierce way she had been riding him, driving him on and on.

She gathered all of the provisions together, though the stench of rotting flesh, offal and spilt blood tainted the air. She would be away from the spot in the morning, before carrion birds began their work.

She thanked the Gods and their bones for the food, and then thought the worst of herself for the prayer. These people had become food for dogs so that she might pillage the meagre leftovers of their livelihoods. The thought made the meat taste bitter and the fruit, bland.

Leste set about burying the family, but the ground was too cold and hard, and she had no good tools for digging. She searched for stones to build them cairns, so their corpses might rot in peace, no longer disturbed by scavengers, but though the ground was hard, there were no good stones about.

Tears pricked at her dry eyes as she used her sword and strength to hack the wagon down into a crude pyre. It was a long and tiresome task. She dragged the bodies onto the pyre, trying not to stagger, curse too much, or fall prey to her tiring muscles.

Sweat mingled with the tears that flowed down her face.

She set the pyre alight just before nightfall, and stood away from it, muttering a few words of prayer to send the souls of the family on. The smell of offal, death and sweat clung to her; she wished nobility were not so hard on the body and the soul.

*

On the fourth day, she rode in ripe clothes, wishing she had paused to pack a change of gear. She had only expected to be gone one day and a night, at the most. The idea of a long pursuit had never entered her head. She’d just gone for it, and hoped it would be enough. It was not.

Khale and his captive were nowhere along the horizon. The rain came down as a light drizzle; it was not hard to ride through, but its prickling, cold persistence wore on Leste’s spirits as the day went on. The sky above was flat and grey, and no darker or light patches showed, no gatherings of storm clouds. Some thunder and lightning would have broken up the damp monotony, but they did not come. The air remained moist and humid, until, finally, it broke on the fifth day. She smiled.

A storm would slow Khale. He would have to stop and rest while the winds howled and the rain lashed down. She could make up for lost time. But she did not.

The storm’s ferocity softened the ground, and her horse went all the slower when lashed by wind and rain. She could feel the animal’s trembling breaths as thunder tore across the heavens, and she had to stop and calm the beast so it would not throw her to the ground and bolt. When the storm finally abated, no tracks were to be seen in the sodden ground.

Leste’s horse trudged on through the subsiding rain, and Leste thought on how many mistakes she’d made in a few short days. In another world, she hoped, it had gone better, and she was already returning to Colm with Milanda, to be feted and praised by the people, while Khale’s corpse rotted somewhere in the wilderness with a great wound in his guts. But that world was not this world, and she knew that no wishes, nor dreams, could change that fact.

After another long, tedious, miserable day, she dismounted and tried to make a fire with wet wood and kindling. Rainwater had seeped into the kindling box during the ride through the storm. Leste did not scream, she just stared at the wet fragments, emptied the box onto the ground, and then aimed two sharp kicks at the fire that would never be.

Rain mixed with tears instead of sweat this time, as she let out a low, soft sob.

Chapter Fifteen

The farmstead came into view as a welcome sight.

It would be well to stop for the night and rest before carrying on, Milanda thought.

There were lights in the farmhouse and a family who must be supping their last meal of the day, or about to turn in and sleep for the night. A malnourished guard dog raised its head from the shadows, trying to growl, but at one glance from Khale’s eyes, the mongrel slunk away.

“Don’t hurt them,” Milanda said.

Khale said nothing in response. He went up to the door and banged his fist hard upon it.

“Please,” said Milanda.

Khale sighed as the door opened.

A short, ruddy-faced man in threadbare clothes peered out from the candlelit interior. His eyes widened as he beheld Khale standing tall and almost as broad as the door. He took a step back and winced, stiffly favouring his left leg.

“What is it, Eunan?” came a voice from inside.

“Nothing, love,” the man said in a dry voice.

Khale spoke. “We need food, water and rest for the night. And a horse for the morning.”

Eunan nodded.

Milanda stepped out from Khale’s shadow. Eunan’s eyes fell on her, and he seemed to relax somewhat. “We have a little to spare for you in comfort,” he said, “not much.”

“It will be enough, thank you,” Milanda said, entering the house. She could feel Khale’s weight behind her and his eyes searching the open space they entered for threats. There were none.

The ground space of the house was for dining and cooking while there was a ladder leading to an upper floor, where the family slept.

“I am Milanda of Colm,” she said to the mother and two girls at the table, their eyes wide, their food sitting undisturbed in earthen bowls. “And this is Khale. We are travellers and would be most grateful for some food, water, and a space to sleep for the night.”

The women looked at one another and then at Eunan. The man of the family cleared his throat. “Please ... please dine with us. We have some broth and bread to break with it. We have hay in the barn for you to rest upon, if it please you.”

Milanda smiled at them. “It does, and thank you. You are most kind. And I would be grateful for a change of clothes if you have it to spare.”

Her nightclothes and embroidered slippers were filthy and worn down to rags.

Their wary eyes barely left Khale as she spoke. He seated himself at the table, and his heavy shadow cast itself as a looming giant in the candlelight. Milanda sat with him and the meal passed in silence.

The broth and bread made Milanda’s stomach feel better, but she feared the look in the family’s eyes as Khale devoured what he could. None of them tried to stop him, but she could see how this was curdling the little goodwill their hosts had towards them. There was something else too: a chair at the table was empty. A small chair, with a bowl of broth sitting before it half-eaten. Milanda wondered who it belonged to.

After the meal, one of the women brought Milanda a change of clothes. The cloth was thickly-woven and the seams were sewn with woolen thread, which she hoped might help in keeping the chill of the nights out. They also gave her a pair of sturdy leather shoes to wear.

Eunan led them to the barn and eased open the door. It reeked of manure and old hay. Khale stepped inside and shaped a nest from straw for Milanda, and she lay down in it gratefully. She watched as Eunan and Khale exchanged cold glances, not speaking, and then the limping farmer closed the door so they could sleep.

Milanda knew, as tiredness washed over her, that Khale would not sleep. He would stay awake and watch over her. For some reason, knowing that made her feel safe, even though she knew what he was. There was a weird comfort in having a man with a demon’s soul as guardian. The last thing she saw as she drifted off to sleep was the cursed yellow of his eyes.

And she

dreamed of tasting his rough tongue inside her mouth, of a raw pulse running through her body as his coarse fingers scrabbled over her back. Of his nails raking trails in her skin before taking hold of her backside and squeezing it hard enough to bruise. His devil-bone beating its fat head upon her bare abdomen, weeping a trail of clear fluid before he touched the tip of it to her, in the place where she was at her softest and had yet to be broken. She wanted to gasp a little as he moved into her with a single, brute stroke, and felt herself closing around his manhood like a small, tight hand and holding him there. His arms, stout and firm, were holding her down. She could not escape him. She did not want to.

He would bite hard at her neck and the hollow of her throat. She would cry as teeth and tongue made her wet and sore. A heat began to stir inside her, building and building. She kicked and pushed against him, wanting to feel him push back. Her breath caught in her throat; a tempest was growing beneath the surface. It was coming. She clung tight to him. She came. It hurt very much. There was blood, and they were done.

She awoke in the night and stroked her fingers between her legs at the memory of the dream. She heard him say something, thinking she was still asleep.

“How did you keep one soul so clean in a world like this? This life, the nightmare that none of us will awaken from, how?”

Not so pure and clean as you might think, she thought with a smirk.

“How did you do it, Alosse?”

Her amorous musings congealed inside her, turning to a cold, hard weight of guilt.

Father …

She went back to sleep and had no more dreams.

*

In the morning, they arose and readied themselves for the journey. The farmer let Khale take one of his horses. Milanda felt bad for the man and his family. They looked terrified for their lives, but Khale had listened to Milanda. No lives had been lost or taken here. They would go on and leave these people in peace.

She saw the boy coming at her from around the side of the barn.

He clutched a small axe in his sweaty hand, and his face was drawn but his eyes shone, determined. As he ran through the thin grass, he made slightly less noise than the wind of an oncoming storm. Her legs became stone, and she could not move.

She did not know what to do.

The eyes of the family were calm.

Milanda watched Khale’s sword come unslung, and then he was turning with the blade flowing outwards like a part of his arm. She heard the screams of the mother and sisters. She saw the look of horror on the farmer’s face.

This boy should have been sitting at the table last night. It had been his bowl of broth that was abandoned. He might have slain her in the night, if Khale had not sat on guard.

Milanda felt a sickness gathering in her gut as the scene before her came to an end. Khale’s blow bit deep into skull, crushing bone and driving its splinters into soft brain. The boy stumbled and fell, empty-eyed, dead before he hit the ground. The spasms his body gave out were those of nerves hardening into paralysis. There was the smell of piss and faeces as his frail body emptied itself one last time.

The mother’s cries split the damp morning air.

Khale did not move as the mother, then father, then sisters came rushing to their fallen kin. They cradled him in their arms with the gentleness given to a newborn—and newborn he was, to the realm of the dead. Milanda looked at the corpse and the family. She was shaking and felt like she could not stop shaking.

“You knew he was there,” she said to Khale. “You knew he was going to come at me. You didn’t need to kill him.”

“Life kills, not I,” Khale said. “He made his choice. They all did. They would have seen us dead in the night and buried our bodies where none could find them. A boy should not try to be a man before his time, if he wants to live to be a man. His father should have known that, taught him better.”

“You didn’t have to kill him.”

“No, I didn’t, but I did,” Khale said. “Never forget who I am, girl. Most killers are made, I was born this way.”

Chapter Sixteen

Khale and Milanda travelled on towards Traitors’ Gap. The going was much easier on horseback. The farmer’s family had not protested as Khale took some small provisions for themselves and the steed. As they passed through the decayed ruins of villages, where the eyes of starved skulls watched them from the dirt, Milanda found herself glad of the dry, salted meat and water-bags though she hated the way it had all been taken.

Hunger made the horse’s feed smell good, at times.

The wild grass wore away to withered land. Everything seemed layered in coatings of red and yellow grit that danced in the wind’s fingers.

They pressed on. Khale told her there were people out here who filed their teeth, so they would not need to cut the meat they caught. And that the meat they caught was that of travellers and lost wanderers. Out here, there were none of the few laws that governed the Small Kingdoms. This stretch of barren land was a boundary between the Small Kingdoms and what lay beyond the mountains. If all of the barons, lords, and kings knew there were worse things waiting out there, they never said so, but still they left this nameless strip of desolation unmolested.

The old legends held that the mountains were ancient pillars, keeping the skies of the world from falling down on its peoples’ heads. And the same legends said that beyond the heights and weather-carved wynds of the mountains stood the lost dwelling place of the Over-Kings: Anaerthe Morn.

Milanda glimpsed small, hairless vermin scratching in the dirt before fleeing into their burrow-holes when dark-feathered carrion turned overhead, ever watchful for the blood and death that would mark their next feeding ground. She could not forget the face of the farmer’s son: the fierceness and hate in his eyes, followed by the shock then emptiness as he was struck down. Khale had saved her life, but the boy’s death made her skin crawl. It should not have happened that way.

“We are being followed,” Khale said.

“By whom?”

“I have an idea, and it is not one I like.”

“What do we do?”

“We draw them out. Take it slow across the desolation. They will come on us in the night, and I will make them wish they hadn’t.”

More killing, she thought, more death.

She wondered if it would ever end.

*

The night was dark and the sky remained as dull and overcast as ever. Milanda could not remember the last time she had seen the stars shining clear. It felt like a long time ago, even though she knew it was not. She looked at Khale and wondered how it went with him.

“Where are we going, Khale? You haven’t told me yet.”

“That’s because I don’t want to.”

“Then tell me a story, at least.”

His eyes glowed in the firelight, making her stomach lining crawl.

“Do I look like your nursemaid?” he rumbled.

“No, but you have lived a long time. You must have a lot of stories.”

Khale looked at her. The colour of his eyes seemed to shift, becoming heavy with the rheum of old age.

“Stories. Yes, my life has many ... stories. Very well,” he said, “would you like to know who I am, girl? Who I really am?”

She nodded, although she didn’t like the cruel tone edging into his voice. His demon-soul was showing itself.

“I was born when the sun in the sky was still white and newborn. I sailed the seven seas of the world and crossed its lands. I stole and I killed because that’s what I do. And then I saw her: a girl, not much older than you are and just as innocent, or so she seemed.”

“Did you fall in love?”

“No,” he said, “I raped her. I was the first man to do such a thing. I stole into her home after dark. I saw her. I liked what I saw. I took her, there and then.”

Milanda didn’t say a word as he went on. “It’s all a lie, you see. I know my legends well enough, because I made most of them up myself. I never faced

Death in battle. Death is the sound of your last breath, your heart failing, no more than that. It doesn’t dress up in a black hood and go hunting for near-corpses to harvest for some golden hall in the sky. Death is your last lover and your last friend. I thought that I was Death back then, as I cut my way through life, not caring for this soul or that. I did as I pleased. So I raped her in the dirt, and she screamed at me and scratched my face.” He lifted his fingers to his face, feeling for the ghosts of old scars.

“And then she spoke before I slit her throat. She said, “You will live to see the world you have created this day, and how it will come to nothing.” It sounded like some whispered madness to me, in those days. I didn’t understand, nor think anything more of it, until the night that came after. My eyes betrayed me. They had become as you see them now. I can still hear the screams, those people screaming that I was possessed by a demon from Hell.

“Perhaps they were right. No, they were wrong. I was much worse than that. Because they hounded me and they slew me, but then I came back. I hunted them down for doing that to me. I tortured some of them for weeks, fed them their own entrails and strangled them. I spent years adrift in murder and blood.

“When I had slaughtered enough, I began to search and to study. I needed to know what had been done to me. It took a century for me to acquire the knowledge of what had happened, but I could not find the words of the curse she had laid upon me. That is until I spoke to one very old mage, who told me that the words of the curse died with her. Every witch and mage has their own language for conjuring with, which they tell to no other. Such a language is a part of their soul. Without her words, no counter-spell could be woven. I finally understood what she had done, and I heard her laughter in my ears that night. I am damned to Life, not Death. There is no greater punishment a man can endure. I cut the mage’s heart out when he told me this. He did not deserve to die, but then I do not deserve to live—so what did it matter if I roasted his insides and made them into a meal, eh?”

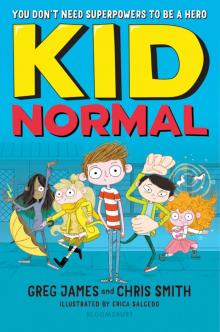

Kid Normal and the Final Five

Kid Normal and the Final Five The Sceptre of Storms

The Sceptre of Storms Made for the Dark

Made for the Dark The Sword of Sighs

The Sword of Sighs This Darkness Mine

This Darkness Mine The Door of Dreams

The Door of Dreams All Things True

All Things True The Stone of Sorrows

The Stone of Sorrows The Oeuvre

The Oeuvre Zombies by Moonlight

Zombies by Moonlight Lost Is The Night

Lost Is The Night Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1)

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One)

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes

Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes Kid Normal

Kid Normal