- Home

- Greg James

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) Page 5

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) Read online

Page 5

It was small wonder that the world was slowly dying around a people who sowed its soil and waters with nothing but bile and poison. He paused to hawk a gobbet of alcoholic phlegm onto the floor.

“Therein lies the truth,” he said to himself, admiring the wet stain.

And what of the Four, was their strength withering like autumn leaves? Could there be something else reaching out into the world? How did the old words go?

And though we dwell long in the Shadows of the Four, we shall fear no Other.

Did it mean there was something more beyond the Thoughtless Dark?

A Greater Darkness?

Timoth finished the dregs of his wine, feeling little courage flowing through his veins. His work for the night was not yet done. He got up and shuffled to the cupboards, where he began to search among jars, phials, and canisters thick with the dust of disuse. So much learning, so much knowledge, so many ways to make the world a better place—all lost, all ignored.

The world was falling apart, but rather than do something, the common people spat on others and called for blood. And blood they’d had—precious blood—belonging to those he loved.

When he found what he was looking for, he clapped his hands together and rubbed them fiercely. This was no flagon of wine for him to drown his sorrows in. This was something to be done in memory of his murdered family.

Something that would never be forgotten.

But, there was a sacrifice to be made and though it was not a great one, he nevertheless found it hard to take. For the spell to work, it was a small matter of cutting off the remaining two fingers on that hand.

A small matter, he thought bitterly, as he ground up the necessary dried roots and herbs with pestle and mortar.

Afterwards, he sat with the knife in hand for long hours, bringing its edge down to touch the skin and then withdrawing it quickly. He got up from the table. He paced back and forth. He drank more wine. He cursed. He cried. It was not the loss of two more fingers that hurt so much as the loss itself. For so much had all ready been taken from him.

“Hylde, forgive me,” he whispered for the second time, remembering the shouts of the macabre crowd, their desire to see his loved ones become burnt-up candles of flesh and bone. Yes, he remembered the children; how they laughed and danced around the flames.

He had seen the fire reach up its fingers and caress his bloodkin until their skin blackened, until it fell away, and their screams were turned to ashes and silence.

And still the children had laughed and danced.

With the memory in mind and tears in his eyes, Timoth sat down at the table, took up the knife, and rested its edge against the roots of the two fingers remaining on his left hand. He set his jaw, squared his shoulders and put his weight behind the blade.

It cut cleanly through skin, then flesh, then bone.

Timoth did not scream. He had a strength inside him that few truly knew.

He wept as he picked up the severed fingers with his unmutilated hand, and let them fall into the bowl where the powders waited. The foul mixture was set alight with a muttered word, and the air of his hovel became thick with wild shadows as he bound himself for the last time to the Thoughtless Dark.

Soon enough, the grand conjuration he had woven was complete. Now, he could work his will upon the world as a puppet-master makes his creations jerk and dance and fall with the merest gesture.

The fate of Colm was in his hands.

And he would deliver it to Lord Barneth.

Chapter Nine

The man returned to his rooms and sat down heavily in a chair. He had seen things tonight that he never thought to see: the mirrors, the things that came from them, and dead men walking out of the door as if they were alive. He found some honeyed whisky to drink, and the sweetness as well as the harshness of it calmed his nerves. It worked better than beer and wine, and he was thankful that he was one of the few in Colm who could afford it. Timoth’s creatures would dispose of Khale and Milanda. They were an expensive means to dispose of a brigand and a child, but he could not afford to risk mortal assassins, who might be easily slain or have their loyalties turned by coin. Without Alosse, Colm was ripe for handing over to Barneth, at last.

I have saved so many lives.

A knock at the door interrupted his thoughts.

He put his cup down, and went and opened it.

“Sir, can I speak with you?”

It was Leste.

Murtagh let her into his quarters. “What is it, Leste?”

“I’m going after him.”

“You’re going after Khale.”

“Yes.”

“Leste, I know how you feel, but this is not the way to ease your conscience. Colm needs us. It needs all of us, with the King gone. We can’t lose you to the wilderness.”

“I failed him,” she said. “I failed the King and his daughter. I need to rescue Milanda and bring her back.”

“It can’t be done, Leste. You know how he escaped. He used sorcery. Who knows where he might be? He could be on the other side of the Heart, you realise that? He could be half the world away.”

“He has gone to Neprokhodymh. You know that as much as I. He used sorcery to escape. His allegiance is to the Autarch, and he is taking her Grace there for whatever purpose.”

“That’s as may be ...”

“It’s my duty, sir. I have to go. My honour—”

“Is not at fault, Leste.”

“But it is, sir.”

“You did what you could.”

“Rather than what I should have done, sir. I should have stayed in the room with the King and Khale.”

“Then you would be dead also, and I could not bear that.”

“The King—”

“Is not the child I raised!” Murtagh shouted. “Don’t you understand, Leste? I love you. I raised you, though you were not my own. Death has taken Maerysa and Neal from me, which is why I have done what I have to.”

“Sir?”

“You are forbidden to leave the boundaries of Colm. The order has been given. The men and women of the Watch know that you are not to cross through any of the city gates until further notice.”

“Sir ... Murtagh … you can’t do this to me. I won’t be able to live with myself.”

“You will, Leste, you will. Someday, you will learn how to. We all do, eventually.”

“Father ...”

“You will not go after Khale, Leste.”

“He is only a brigand.”

“Enough. Go home, Leste. Yrena and Osta need you more than the dead and honour do. Go, now.”

“Sir.”

Leste left, and Murtagh closed the door after her, letting out a long, tired sigh. He hoped she would listen to Yrena, if not to him. A lover’s words often bear more weight than a father’s.

She would hate him, he knew that, when she found out about Lord Barneth and when Colm became a part of his kingdom. But she would be alive to hate him, as would every other person in the city who would have died otherwise. Murtagh could live with that, just about.

Better alive and hating me than lying dead on cold ground far from home with the crows as her pall-bearers and worms to bury her, he thought.

He knew what Khale was, though he knew Leste did not believe it. She was still young, she did not understand how strange the world had become.

The old stories told of a great battle long ago, the battlefield it was waged upon stretching for a hundred leagues. On that ground, from dawn to dusk and then well into the night, men, women, beasts and demons fought until the earth was an ordure of blood and churned entrails. Many fell that day and night, more than could ever be counted, and such was the scale of the slaughter and bloodshed that Death himself walked corporeal among the fallen, harvesting their souls.

It was dawn of the following day when Death came upon Khale.

He was the only one left standing, alone, wearied and bloodied. He was only a mortal man back then, a soldier trained and exp

erienced in the arts of war, but still a darkness clung to him; it coloured his blood with a bitter lust for the kill, a lust none of his fellows shared. His fellows now lay about him, carved into pieces, torn apart.

Death came to him at this moment and raised his blade high to lay Khale low. And Khale raised his sword in kind and met the sword of Death with a thunderous crack. The air shook as he turned Death’s blade aside. But Death was tireless, as all Gods and Goddesses are, and he swung his blade down to cleave Khale’s skull again. Again, he was parried. Again, he was denied.

For a further day and night, Khale fought with Death as mongrels and vultures feasted on the rotting slain. No words were spoken. No sound was uttered by either of them. There was only the relentless song of steel ringing out across the reeking battlefield. On and on the duel went; each thrust parried, every riposte answered by counter-riposte.

Only when dawn rose once more over the scene was the struggle decided. Judged a weary mortal by his immortal foe, he was able to take advantage of the arrogance born in all Gods and Goddesses. As Death saw Khale slowing and finally tiring, the God’s gestures became grander, his blade falling only after ostentatious, taunting sweeps and displays of his unholy dexterity were made.

In the small pause between one such blow and the next, Khale struck. He drew a dagger from one of his greaves and drove it into the place where Death’s heart should have been. Death had no heart to speak of—the wound was no more fatal than the bite of an ant—but it was the distraction Khale had needed. Faltering, Death’s black eyes wide at harm inflicted upon him by a mortal, he fell under Khale’s sword. His smoking blade was shattered and his head cut from his shoulders.

Khale mounted it upon the splintered spike of a standard that was trampled into the mud nearby. And as he stared at his black-eyed trophy, he felt a sudden and terrible cold surge up from his heart. It swelled into his throat, choking him as surely as a freezing hand might. And the eyes of Death were upon him as the God’s bloodied lips spoke a curse.

“For what you have done this day, for raising your hand to one such as I, for turning Death’s blade aside, I name you Wanderer. The roads of this world, you shall walk them all. The men and women of this world, you shall know them all. The pain of darkness and death, you shall feel these things always. Yet you shall not die, for you are mine: Death’s Herald. And on the last day of the last age, you shall sound the fatal notes of my Horn and bring all Creation down to nothing. And only then, when all things know Death, shall thou know thy true death and, at long last, sleep.”

And with these words, the black eyes closed and the head and body dissipated as ashes on the wind. Khale was alone on the battlefield. Alone in the world.

A killer like no other.

A warrior stronger than Death.

Murtagh poured more honeyed whisky into his cup, drained it, and then decided he would finish the bottle tonight. “May the Gods and their bones forgive me, and may their Shadows save us all.”

Chapter Ten

Leste stood before the decrepit doorway that led into the Church of Four. The church building was a rude structure of recovered stone, the windows patched with woven straw and dried moss. No light was permitted in the Church, save that which the Fathers and Brothers fostered within its dank walls. Dark and desolate, it towered over all other buildings in its district—bequeathed to the Church by the King in return for their support of his claim to the throne.

She had spent most of the day angrily walking the streets of Colm. The men and women of the Watch nodded their greetings but she could see they were all thinking of Murtagh’s orders. Their eyes were wary and guarded. Their gestures to her were tight and ready, in case she tried to strike them.

Leste performed the four bows out of habit more than faith. She had always felt a disquiet about the Church and its malnourished denizens with their black robes and bowed heads. Whenever their faces were shown, they were solemn and pale, and their gaze turned inward, lost and despairing. They reminded Leste too much of the world outside the walls of Colm: a world that was gradually creeping in through those walls, dulling the thoughts and tainting the lives of those who lived here.

She had an idea that the Church existed only to perpetuate the world’s misery, to tie people to it, rather than to ease the pain of those in suffering and to drive away the cold.

Still, she had been brought up in the Shadows of the Four, like every child in Colm, and, for once, she hoped they would hear her prayer, bless her journey as it lay ahead, and curse the enemy she pursued.

Leste crossed the threshold and waited for her eyes to adjust to the scented gloom inside. She could see people kneeling before each of the four idols, presenting the gifts demanded by each of the Four. To Murtuva: a fresh kill. To Chuma: a token of decay. To Voyane: blood drawn by another’s hand. To Mirane: an offering of food and nourishment. Leste grimaced at the smell of the offerings left for Chuma, and the humming song of the flies attracted to the small, dead things at the base of Murtuva’s idol.

Each of the idols was veiled; none but the Fathers of the Church were permitted to look upon them. It was said that eyes of the sculptors who carved them had been cut out and their fingers severed after the work was done.

Sisters and Brothers moved around the prostrate and the weeping, whispering words that sounded as chastising as they were encouraging. One of the pale, black-clad creatures approached her, fixing a vacant stare upon her. She was unsure, at first, whether it was man or woman.

“Do you wish to pray and make offering, daughter?”

They were all shorn of hair when they took their vows and observed the sacraments of the Four. Their bodies steadily shrank to skeletal proportions as they fasted repeatedly, and few made it past their fiftieth year; those who did were whispered to be mages harboured by the Church.

“I have no offering to make. I only wish to pray.”

“Without offering, not one of the Four will listen. What is the substance of your prayer?”

“I have a journey ahead. An enemy to overtake. A child to rescue and return home.”

“Then your offering should be made to Voyane. Blood drawn by another’s hand. Fear not,” the trembling creature said. “I have a knife.”

Leste flinched at the notched blade the Brother drew from the folds of his cloak, and at the way he stroked it, caressed it, and looked eager to put it to use. She let him lead her by the hand to the foot of the idol raised in honour of Voyane.

“Make your bows, my child.”

And she did.

“Now, give me your hand.”

And she did.

“Please, try not to scream.”

He cut across her palm with a swift stroke. She did not scream. She felt time grow long as the pain passed through her body, making her nerves sing and her brain ache. She swallowed the pain, only opening her mouth to let out a few ragged breaths. Leste looked to the Brother and saw how his moist eyes adored the wound he had made.

“You have given of your blood, daughter. Now, make your prayer to Voyane, for she has tasted of you and is now listening.”

Clenching her hands into fists, keeping her head bowed, Leste made her prayer.

Voyane, Blood-Creator, hear my words and seal my oath with this blood spilt. I ride against a great enemy. Give me strength to match his strength. Cunning to match his cunning. Will to strike against his will. In your name will I bring an end to his life and thus my oath will be served and this blood unbound. Murta ashe vey.

“She has heard you,” said the Brother. “I feel it in my blood and bones.”

Leste rose to her feet and left, not sparing a glance or a word for the twisted man. There were stories about the Fathers and Brothers—about how they preached strength yet practiced the worst kinds of weakness. She had seen it in his eyes when he cut her hand.

Truly, what good had visiting that rancid place with its whimpering souls done her?

She sighed, and realised she was still clenching her hands

into fists. She relaxed her fingers, only to stifle a cry at what she saw on her palm, or rather what she did not see. There was no more blood. The wound was a ridged scar stretching across her palm, as if it had been there for many years. It neither ached, nor throbbed as she flexed her fingers and made a fist again.

Her disquiet with the Church and its Gods grew all the more.

*

Leste went home to prepare for the journey. Despite what Murtagh had said, there was a way out that she could try to use. It would be guarded—she had no illusions about that—but she had to try. She loved Murtagh; however, he did not understand what this meant to her.

It was night and dark in the house. She had crept in unshod so as to gather her things quickly and quietly before leaving the city. If she was swift, she was sure that she could pick up the trail and bring Milanda back. Khale might have used magic to escape, but he could not have travelled far if his destination was to be Neprokhodymh.

As she turned to leave, Leste felt eyes on her back. She heard a familiar mouth breathe in sharply.

“I have to go, Yrena,” she said, turning to face her lover.

The words were scarcely out of Leste’s mouth before she saw the pain spreading as dark lines across the older woman’s face.

They had been together for three years. She had been the widow of Murtagh’s last sergeant, Oman, and it was out of respect for his memory that no-one in Colm told too many tales, or spat at them in the street. Yrena was handsome, with fine grey hair and a noble woman’s bearing, though she did not have the breeding.

“No, you don’t have to go,” Yrena said with tears in her eyes. “Am I to lose Oman first and now you also? This is not about what you have to do. You just think you have to do this when really you do not.”

“You don’t understand, Yrena.”

“No. I don’t. I don’t understand why we are so little to you. Why your duty is so much more. You said that you love me. I said that I love you. The boy asleep in the other room loves us both. Why would you leave us behind to die alone in a far-off place?”

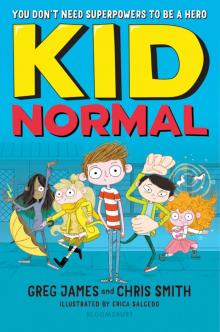

Kid Normal and the Final Five

Kid Normal and the Final Five The Sceptre of Storms

The Sceptre of Storms Made for the Dark

Made for the Dark The Sword of Sighs

The Sword of Sighs This Darkness Mine

This Darkness Mine The Door of Dreams

The Door of Dreams All Things True

All Things True The Stone of Sorrows

The Stone of Sorrows The Oeuvre

The Oeuvre Zombies by Moonlight

Zombies by Moonlight Lost Is The Night

Lost Is The Night Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1)

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One)

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes

Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes Kid Normal

Kid Normal