- Home

- Greg James

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Page 4

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Read online

Page 4

If the White Rider and Gorra had ever come to this World again, she never saw them.

Or, as she thought, they kept well away from her.

O Flame, that’s what he called me, why?

Sometimes, she shouted the question to the trees, hoping to stir him from the Wood Beneath the Worlds. But the only answer was a sighing breeze.

And after three years, she no longer cried at night or ran away from Woran. The old man was growing brittle in his advanced years, and he needed her help. The Beans were the shepherds of the hill. Their nearest neighbours were the Taproots and the Saltwines. The Taproots were farmers of the slopes. The Saltwines were brewers of ale, whose famous Hillshine liquor was sold to the taverns and way-houses thereabouts. The three families had been neighbours in the valley for generations—so many that none could trace a time in their family trees when their children had not known and played with each other from their earliest days. Some even married, so the bloodlines of Bean, Taproot and Saltwine crissed and crossed, back and forth, until there was a web of loyalty and trust binding them together.

Or so it had been, until Woran and Joliah Bean, his only son, went to war. They rode away together, but Woran Bean rode home alone. His lined face was made even more haggard by the sights of war and the loss of his son. Thus, the Bean family became one lonesome old man and his goats. The Taproots and Saltwines grew distant from him, their relationship strained. The girls who had once vied for the hand of Joliah Bean grew older and more matronly. Spinsters of the valley had been a rare enough thing when the blood of the three families had been thick, strong, and vital. Now that it was growing thin, and the children fewer, those who lived through the lengthening winters that swept down from the Northway Mountains grew bitter. Solitude and shadows pressed in upon their hearts and souls.

Sarah had little physical likeness to Woran, who claimed to be her grandfather, which did not endear her to the neighbouring families. In the valleys, they were known for being hardy folk. It was said that one of their number could walk for a day and a night barefoot and naked through a storm and not come down with the slightest sickness. Their hair and eyes were dark, and their bodies were bullish and timber-strong. Sarah was slender. Her skin was pale and her hair was a fine blonde. Her eyes, however, were her most extraordinary feature: glimmering amethysts threaded through with violet. None of the Taproot or Saltwine women resembled her in the slightest, and they often cuffed their menfolk when they caught them staring at ‘the Bean girl’ as she had become known.

Woran taught her how to herd goats, and on the nights when he wept as he thought on how his son was gone and how soon he would be gone too, leaving Sarah all alone, she comforted him. Or tried to. He had comforted her as best he could when she had cried and screamed about wanting to go home, when she had longed for a World he could barely understand. Without him, she knew she would have come to no good end at the hands of the Taproots and Saltwines if they had caught her wandering in the valley. But what would happen when Woran died? She would be cast out, and they would take the land that had belonged to his family for generations. Could she call on Gorra then with those words he had given her? Would he come and help her? Save her? Take her home? Would he?

No, she thought, not for something like this.

I think.

“I have failed my father,” Woran said when he cried, “and my son, my only son. Everything will be lost to Esiah Taproot, or Miria Saltwine. What am I to do, Sarah? What am I to do?”

She held him, and hoped that something would soon happen for the better.

~ ~ ~

The valleys rolled and rippled into horizons patterned by the shadows of passing clouds and brightened by the sun. All except the horizon to the north, where the land became rougher and a mountain range stuck out like jagged, grey-white teeth. These were the peaks of the Northway Mountains, and through them ran but one pass. It was held by the city of Highmount: a fortress-city built to guard the Three Kingdoms against bandits, the mercenary armies of the Grassland Plains, and beyond that, the fell inhabitants of the Nightlands in the faraway east.

Three walls stand where armies fall,

Three iron gates forged to cast back hell,

Three walls stand against the darkling hordes,

Three walls shall stand for Three Kingdoms proud.

Few understood all of the old rhyme, but it was sung heartily enough and often enough in the taverns of the valleys and in the Three Kingdoms of Brindan, Atosha, and Yrsyllor. As long as the three walls held, there would be peace. As long as the Fallen One slept beneath the Shadowhorn Mountain in the wastes to the east, known as the Nightlands, there would be goodwill among women and men.

But over these last few years, a creeping blight despoiled the valleys. Grass grew, but not so rich and green as before; bare patches of soil showed everywhere, and the shoots that emerged were limp and yellow. Few of the goats, sheep, and cows deigned to eat them, and those that did became sick and died. The rest merely grew thin, starving until they had to be slaughtered for meat before they became nothing but skin and bones. Storms and bitterly cold winds became more frequent, lasting into the mid-year months, when the valleys were usually temperate and mild. Whispers were spoken in way-houses and in the Keeps of Earlmen alike. Tales travelled of fighting beyond the valleys in the Grassland Plains, of the Kay’lo bandits becoming bolder and the robber-barons more vicious when their mercenaries waylaid merchant wagons. Stories were spoken in hushed tones of five black riders seen on the horizon when the sun went down. Women and children complained of hideous nightmares, and men awoke in the mornings sullen, sour-faced, and unrested. As time went by, many watched the roads, waiting for word to come from Highmount of something happening in the east.

~ ~ ~

It was late in the afternoon when Sarah herded the last of the goats up the slopes to the hill and into their pen. Barra, Woran’s mongrel dog—a rag-eared, rat-faced little mutt—bounded about, hemming in the bleating goats as Sarah drove them on with shouts, clashing the base of her staff against the stony ground.

So little grass, she thought, and now the soil is thinning too, just like when the Wood Beneath the Worlds was tainted by Yagga.

“Save us. I hope this blight passes on soon,” she said to herself.

Was this because of Yagga? What did Gorra say?

Her rot has spread too far and too deep...

Shadows were lengthening all about her, and the low sun was tingeing the sky to a deep, lustrous gold that would soon darken into night. She increased her shouts and stamped her staff as if it were a third leg, beating it hard upon the rocks and shoving it into the behind of a dawdling goat when she had to. The sun was already making a dark thing of her home and its hill.

I already think of it as home, she thought, after only three years away.

“The grass grows fallow, storms come and go, and now the night becomes long and dark,” she said to Barra as he darted past. “What will we do, eh, Barra?”

He made no yip in reply.

Sarah realised she could no longer see him bounding about among the gathering shadows and goats, as he had been. Brow furrowing, she turned, and then turned again, casting her eyes across the slope they had just ascended. She saw nothing untoward but nothing of Barra either.

“Barra? Barra!”

Silence. And the wind.

“Barra, where are you?”

Sarah looked to the goats, which were gradually trotting away. If she went looking for Barra, the goats would lose themselves in the dark. Without them, they would have no livelihood. No meat, milk, nor wool to sell at market in the village.

“But Barra ...”

She whistled and called for a few minutes more. He was an old, greying dog. If he fell or was wounded somehow, he would die rather than recover, she knew that well enough. A goat began to make its way past her, slow but sure. Sarah turned and pushed the animal back up the slope towards its fellows. Casting one last look back down the slopes and in

to the curves of the valley below, Sarah herded the goats home, biting back tears and the urge to run off into the dark.

~ ~ ~

“You’re quiet tonight, Sarah. Is it about Barra?”

She nodded as she ladled autumn stew into her mouth, her shoulders slumped and her head bowed.

Woran Bean blew out through his whiskers and stroked his bristled chin. “He may be all right. He’s old, but he’s a smart dog. If he got himself lost, he’ll lay low until the morning. We’ll find him, or he’ll find us when we take the goats out.”

“I hope so,” said Sarah, gazing into the distance.

Her eyes suddenly turned on Woran, who gasped at the way they shone in the light cast by the fire.

“Woran, do you know what’s causing the blight? Stirring up the storms and making the nights so long and cold? I’ve never known a winter like this before, even back home, and we are only at the beginning of it.”

Woran stirred his stew with the wooden ladle, studying the eddies and whirlpools he made with mutton and rooty chunks of vegetable. He sighed, sat back, and ran his hand through his thinning hair. “I’ve never seen the like before either, Sarah. So no, I don’t know.”

“But you’ve heard about something like this happening before.”

A small smile crooked Woran’s lips. “You’re a clever one. Sly as Joliah used to be. Yes, you should have been born to him as true blood-kin. Yes, you should. There are stories, Sarah, from long ago, of such things happening here before, but they are stories only. The truth of a myth or a legend is in its telling, and no more than that. If we went around believing every one of the old tales, we’d all surely go mad and be seeing Fellfolk where there are only shadows.”

“Fellfolk?”

“Those who’ve given their heart and soul to the Fallen One, who sleeps and dreams all our nightmares beneath the Shadowhorn.”

A sudden darkness came over the house. Great black wings passed by the window, engulfing the room in shadow and making the fire’s flames wane weak and dim. A hoarse crow's cry came from outside the door.

Sarah’s face paled, and so did Woran’s.

“Only a night-bird, Sarah. Only an old crow, nothing more.”

But his voice shook as he spoke. They ate the rest of their stew in silence, listening for further cries from the crow outside.

None came.

Chapter Seven

Morning came. Autumn was slowly dying and Winter's footprints could be seen, frost-white and hard upon the ground. Sarah and Woran opened the pen and let the goats out onto the hillside, guiding them down to the slopes below to graze. It was a task usually made much easier by Barra dashing about, yipping and shoving at the hurrying animals.

“I can’t see Barra.”

“Call to him, Sarah. If he’s hereabouts, he’ll come when you call him.”

“Barra! Barra! Barra? Here, boy!” Sarah took a few slithering steps down the hillside and peered into the shadow cast by an old stone that was set in the ground at a severe angle. She detected movement, fur, and the sound of harsh breathing. “Woran! It’s Barra. I think he’s hurt.”

She stepped slowly toward the shadowed form, her staff in one hand. Her fingers gripped it tighter, although she was not sure why. Something about the sound of that breathing—it was guttural, laboured, deep, and sick.

“Save us, don’t let him be dying. Not Barra.”

At her next step, she heard her grandfather shout, “Sarah, no! Get away from there!"

She turned to see him half-running, half-hobbling towards her. She turned again. What she had thought was Barra was emerging from the shelter of the stone. It was mangy and near bald. Grey-scaled flesh showed through withered clumps of black fur, and its eyes were as yellow and tainted as its teeth. Brown ropes of drool hung from its jaws as it came out, grumbling in its throat. Sarah could smell it.

Save us, she thought, it stinks like something dead.

Then it opened its rancid maw, howled, and leapt at her, knocking the wind from her lungs. Her staff fell from her hand. Black blossoms and shining white light swam across Sarah’s vision as she dug her hands into the fruit-soft flesh of its throat. She could feel tendons and muscle straining, and drool spattered her as her fingers sank into the rotten meat of the thing’s being. She could hear Woran’s shouts and was sure that the beast was twisting and turning as the old man beat at it with his own staff and kicked at it with his feet. The eyes of the thing, though yellow and ripe like plague pustules, burned into her as she fought against it. Eyes that knew her. Eyes that spoke without using words.

“I see you, O Flame. I know you, O Flame. I will slay you this time. Thy Fire will rise no higher. I will make the Light go out.”

Sarah felt her arms weaken and the breath of the thing came closer: hot, rank and wormy. Its teeth ached to tear into her throat and end her life.

What have I done? She wondered. Who does it think I am?

“You are the last. The only one left. All shall fall without thee, O Flame!”

Then, there was another sound, familiar and welcome. The weight of the lupine thing was torn from her, and she could breathe and see once again. Getting up, rubbing her arms and legs, she saw what had happened. Barra was there, struggling with the creature, his jaws locked into its throat, pulling, shaking, and tearing. It kicked out feebly, biting and snapping at thin air, knowing it was done for. Woran rushed to Sarah’s side and embraced her. “It was intent on you; it didn’t see Barra coming. So much for that … Fellhound.”

"What is it?"

“A Fellhound, Sarah. Something that hasn’t been seen for a very long time. Look at your hands.”

She did, and felt her stomach turn. They were sticky and soiled with brownish muck and crumbs of dead flesh.

“I was trying to hold it off me. I could feel my fingers sinking into it. How could that happen and it still be alive?”

Woran looked at the creature on the ground, already attracting flies and worms to it. “Because it was not alive. Nothing can truly serve the cause of the Fallen and live.”

“But it’s dead now.”

“No. Wounded. Weakened. Nightfall will heal its flesh and then it will come for you again.” Woran grabbed her by the shoulders. “Bring the goats back up into the pen now. We must get back to the house. There’s not much time.”

“But it’s barely midday—”

“Don’t argue, Sarah. Just do as I say.”

Woran’s eyes cast about from horizon to horizon. Sarah saw in his face that he was in fear of something—something far worse than the twitching Fellhound.

~ ~ ~

Back at the house, after herding the goats back into their pen, Sarah found Woran poring over an old book. Its leather covers were peeled and split, the papers in it barely held in place by ancient gum and wood-glue. She walked closer and saw the woodcut graven onto the page in stark black lines. Though it was an angular and rough image, she recognised it easily enough as the beast that Barra had taken down outside. There was something else in the woodcut—a tall, dark human figure.

“What is it? Do you know?”

“I’ve never seen one before, but I’ve heard tell and read enough of the old legends.”

“But you said legends were only true in their telling.”

“I did, and the Mother strike me down but I feel like my foolish words were what brought that damned thing here, although I know that’s not the truth.”

“So, what is that other thing with it?” Sarah pointed to the woodcut.

“A Fallen-born, Sarah. A creature of the Nightlands, bound to the service of the Fallen One in life and in death. The Fellhounds are their hunting dogs.”

“Just what is the Fallen One, Woran? You’ve never told me about this before.”

“It’s just a legend, an old, old legend—and that’s how it should be and should stay. A story to frighten children, but that thing outside was real. Mother save me, I touched it. And save us from the stink of it. And that o

f its masters.”

“How could it get here? You told me the Waste was a long way away, and there’s the Northway Mountains and Highmount to defend us here.”

“I don’t know how it came to be here, Sarah. I wish I did. But I know one thing for sure.”

“What’s that?”

“That we must go—before tonight, before it gets dark."

“What? But we can’t. Not tonight. Not just like that. What about the goats and the house?”

“We can and we will, Sarah. I knew this day would come the very day I took you in.”

“It came for me, is that what you’re saying? Do you know that for sure? And you didn’t tell me that either, why?”

The old man smiled tenderly, reached out and stroked a grandfatherly finger along her jawline. “Yes. I'm sorry, Sarah. I knew. I found you and I knew it was no accident. You are not from this World. You are from somewhere I don’t know. A place filled with things and people that sound fearful and wondrous all at the same time. And yet, despite that, you look like her.”

“Who?”

“A woman I loved. She would have been my wife, but war took her from me as it did my son, Joliah. You come from somewhere so very strange, and yet your face is the youthful mirror of one that is engraved upon my heart.”

“That’s why you kept saying we are the same.”

Woran sighed and nodded. “Yes. I knew for you to come to me must mean something would happen, and that you would be at the heart of it. And so you are, and so we must go. War is coming to Norn. I don’t doubt it, but I won't lose you to it. I will not see her face die twice in my lifetime. Sleep now. I will take the watch. I will burn that wretched Fellhound before it can revive, and I will see we are not surprised by its masters.”

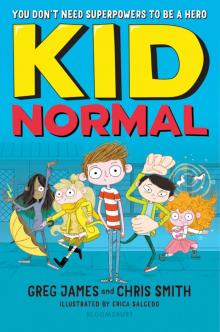

Kid Normal and the Final Five

Kid Normal and the Final Five The Sceptre of Storms

The Sceptre of Storms Made for the Dark

Made for the Dark The Sword of Sighs

The Sword of Sighs This Darkness Mine

This Darkness Mine The Door of Dreams

The Door of Dreams All Things True

All Things True The Stone of Sorrows

The Stone of Sorrows The Oeuvre

The Oeuvre Zombies by Moonlight

Zombies by Moonlight Lost Is The Night

Lost Is The Night Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1)

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One)

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes

Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes Kid Normal

Kid Normal