- Home

- Greg James

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) Page 3

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) Read online

Page 3

Alosse clapped his hands one final time. “The feast is ended. We shall speak on the morrow, Master Khale. Tonight, the hospitality of our palace is at your disposal.”

Leste did not like the idea of Khale remaining within the castle walls, not one bit.

Chapter Five

Khale sat alone in the bedchamber that had been given to him for the night.

The Lady of the Watch was on guard outside. She had made no bones about the fact that while he might be here at the King’s request, he was not trusted. He was sure she would stand there until dawn if she thought it necessary.

Loyalty, he thought, the first and the worst of all sins.

A table was set in his chamber with fruits, cold cuts of game and white meat, as well as flagons of spiced wine. Khale supped from one of them. It was overly spiced to cover its cheap, watery bitterness.

Twenty thousand golden-eyes, he thought. I wonder that Alosse is able to make them believe he has that much in his coffers. But that is a King for you; the lies that fall from his lips are treated as gold coins by his subjects. And between them, who is the greater fool?

As he sat on the bed musing on this and polishing off the bad wine, the door to the bedchamber eased open with the slightest creak. Looking up, he saw a young girl stumble in, as if she had been pushed from outside. Her eyes were red from weeping. The door closed behind her and Khale barely discerned a whisper from outside.

An order by its tone, no doubt.

She looked at Khale quickly, and then looked away, studying the worn tapestries on the walls and the ornamented chests that all looked as if they had been neglected and left there to rot. Khale could see her arms and legs were too thin, and that some bone showed around her rib cage. She was dressed in silks, but he could tell she was not used to them. They must feel strange on skin that is used to a poorer cut of cloth, he thought.

“Eat.” He gestured with his flagon to the table.

She looked at him. Her fingers, wringing themselves hard, were too thin as well.

“I said eat.”

Slowly, not taking her eyes from him, she went to the table and began to pick at the fruit; first, some grapes, then an apple and an orange. Khale watched her, knowing the reptilian yellow that flickered across his eyes must make her want to leave, even if nothing else about him did.

He wondered why she was here. She had been sent to please him, that much was obvious, but no girl would agree to do so without much money being offered. Or it could be more than that: a father, brother, or husband to hang at dawn by the King’s order, whether he had done wrong or not.

Yes, he thought, the girl is scared, but not just for herself.

She wore her beauty as a faded mask. Her long black hair was not as lustrous as it might once have been. Her eyes were too big and white with hunger to be seductive. But her lips were becoming wet with colour as she bit deep into another orange and drank heartily from a flagon.

Wine gives courage to women as much as men, he thought, and he waited while she finished her small feast. Then, she came to him with halting steps; frightened and a bit drunk. Her shaking hands found his chest and fumbled at the rough stitching of his furs. Khale took her hands in his and removed them, shaking his head.

Her eyes, wide and begging, went to his.

Please don’t send me away. I must do this. I have to. That is what they said.

He nodded and undressed them both. He laid her down on a bed worth more than the lives of her whole family. For the next hour of her life, Khale was gentle and no-one was more surprised than he.

*

Not long after the girl departed, the door opened once more.

“It’s been a long time, Khale,” Alosse said as he came in.

“Alosse,” Khale answered, gnawing on a rich cut of game, “you have grown old, and you smell of piss.”

The King smiled back. “Age comes to those of us not as blessed as you.”

“I’m not blessed, Alosse, never have been. I do not call it my curse lightly.” Khale cleared his throat and swallowed a mouthful of wine. “Your messengers were well chosen. They had no idea.”

“Indeed. Your demands mortified them, you know.”

Khale got to his feet, stretching out his arms, back, and legs. “The girl is an idealist. I can see it in her. It burns like fire. That fire will soon go out though, once she’s lived a little.”

“Fire, yes,” Alosse said. “That was a good trick with the fires in the court when you came in.”

“A simple but effective conjuration,” Khale said. “Men grow no less superstitious as the world turns under their feet. A touch of darkness is the root of all fear.”

The King harrumphed. “No matter. To business—we have much to discuss.”

Khale sat down. “So, it is true. You finally got the attention of the Autarch.”

“I did, though it took time and a desperate need.”

“And a daughter who has not been despoiled. How old is she? Eighteen. For keeping her pure so long in this world, you have done well.”

The King’s face strained for a moment at Khale’s words. “It has not been easy, but it has been done. She is of age, and the time for her purpose is at hand. I need you to do as we agreed a long time ago.”

“And what is to happen here?” Khale asked. “You are here for a reason, are you not?”

“My death, Khale,” King Alosse said. “You know that. It is what must happen here, between us, tonight.”

A moment passed in which both men’s eyes met; one with its xanthic taint, and the other with its rheum and bare mortality.

Khale sighed and stroked his fingers through his unwashed mane. “Aye, your death, and then?”

“You take Milanda to Neprokhodymh.”

“Your daughter’s life will mean the end of your line and your blood, Alosse.”

“Truly said, but in exchange for the soul of one so pure as Milanda, the Autarch will see Colm spared for a time.”

“They will come for the city eventually, Alosse. Barneth and Farness covet this land. You’re buying your people a breathing space, no more.”

“I know, I know. I hope and pray it is enough. A new leader will arise, I’m sure of it, and the people will follow him ... or her. For my city, my people, love for my own blood must come last.” His voice dropped to the barest of whispers. “Milanda must die. She is a sacrifice that I must make.”

The old King’s eyes were steel points in the dark of the room. “Do it, Khale. I cannot bear this life much longer. I should have died years ago. I’ve been clinging because ... because there’s been nothing else for me to cling to. Do you know how many years I’ve been resting my backside on that bastard throne?”

“No.”

“No, you wouldn’t. I’ve been here since we drove the last of the mages into the Heart of the World to die. You know, there’s something I never told a soul. Something that happened to me when we were fighting that blasted war.”

Khale nodded, listening.

“I found him in some ruins. He’d been wounded.”

“Found who?”

“One of them, Khale. A mage. You should have seen them. They were all like him, the wounded one I found that day. Oh, he was immaculate. Perfect. A beautiful creature. I killed him.”

“Really, Alosse? You surprise me.”

“He’d never done anything to me, and I put my sword through him without a second thought. Do you know why?”

Khale said nothing as the King went on.

“Life wounds young and old alike, Khale. You know that more than most, but few will admit to it. It doesn’t discriminate, the world we live in, though we like to think it does. That’s why I killed him. He was beautiful and his eyes were so peaceful, even with all that blood pissing out of his side. He was beautiful. He’d done me no harm. I couldn’t stand to look at him. I couldn’t let him live. Not one moment longer. He had to die.

“Get out, Beauty, that’s what I thought to myself as I di

d it. I thought, go from us. No longer make us see and feel how low-born, lost and petty we are. Leave us our spite, our bitterness and our malice. Leave this world to us alone.” Alosse sighed and was wracked by a prolonged bout of coughing.

“I was young once, and when I was young, I was a hero. You were there. You remember it, don’t you? The battles. The glory. The swords in the wind.”

“I do.”

“And then I became this ... thing. I grew old, and I became an old man. I wasn’t a hero anymore. Nothing can replace that, you know: not wealth, not beauty, not wonder. Not even love. I could not find it in myself to weep when Milanda’s mother died, not a single tear. I can’t remember her face anymore. And ... what was her name?”

Khale shrugged.

Alosse went to the table and poured himself a generous cup of wine. It spilled as he lifted it and soaked his beard thoroughly as he drank it down. “I was a hero, Khale, and I’ll not leave this world with a lie as the last words on my lips: it never got better. It never got any better. It never could, and you knew that didn’t you?”

“I did, Alosse, and you would not listen when I told you so.”

“Get on with it, then. I’m done talking ... done with everything.”

Khale came at him and drove a knife into the King’s heart. “Goodnight, old man.”

He caught Alosse’s body before it fell. There was a sharp gasp, and that was all. The light was gone from the eyes, and nothing stared into nothingness.

The King’s killer stood over him for a moment as he cleaned his knife blade, swiping it roughly against his furs. He re-strapped his two-handed sword across his back. Then, with a whispered word, he too was gone. He disappeared like a ghost.

*

Leste found Alosse. He had been too long alone with Khale, and when she listened at the door, she heard no conversation. When she entered, she saw the dead old man hunched over on the floor, bleeding into the thick bearskin rug laid over the flagstones.

“My liege ...”

She held him and her hands came away dark and red.

Tears pricked at her eyes.

I failed him, she thought, I was on guard. He’s dead. I failed him.

She cradled the light, frail form of the King and wept as if she were a mother holding a stillborn. She should never have left them together.

“I will find him, your Grace,” Leste swore. “I will find him and I will kill him for this.”

Chapter Six

There are whispers of iron cities and great roads before the white fire came, but that world is gone now, and what came after is remembered as a night of cold and darkness that saw our people come close to dying out forever. After it passed, we were little more than savages, dwelling in caves with precious few memories of the old world—but something did linger on. Our hands found stone and wood, and bringing them together made fire come into the world again. We made weapons of flint to slay the animals and cooked them over the fire, though we could not help but think we had done this before; and in the taste of their blood, other memories awakened.

To children, women, and to elders came dreams, visions, and voices that spoke without words. The men were shown how to shape the world around them: to fell the trees and to work the stone, creating walls that could trap the fire’s warmth. All the while, the elders and the young continued to dream and to speak of what could be achieved. From their words came the first castles, the first kingdoms, and the first kings. Our people were divided into rich and poor, the exalted and the hated, the damned and the lost.

And from the words of the seers came worship and sacrifice as we learned of the Four who watch over us: Murtuva, the Last Breath; Chuma, Plague-Father; Voyane, Blood-Creator, and Mirane, the Starv’d One. For only with darkness can darkness be fought. Light failed our ancestors, and so we abandoned its worship forever.

Though some say there are places in the land where worship is given over to Another—neither of the light, nor of the dark—who dwells beyond the shadows cast by the Four, and such places lie deeply buried beneath isolated henges of disfigured stone ...

*

Milanda closed the book for a moment. She loved to read, and the stories of old were her favourite. They told of a world so much more exciting than the one she endured day by day. Eighteen winters to her name and she had not been outside of the city gates. In truth, she had not even crossed the moat from the castle into the city itself. Her life had been these stone walls, the wan light that filtered in through its windows, and the faces of men and women so much older than she.

When she awoke in the mornings, there was fruit, meat, cool water, and warm milk waiting for her, as well as fresh clothes. The clothes were always plain and dull. The dresses and battle-armour of the women in the stories were never presented to her. When she wished to bathe, she would be bathed by attentive Sisters from the Church of Four. They were the shadows that haunted her steps whenever she left her chambers and the heavy iron door that sealed her in there at night.

She daydreamed about the mage wars, the demon-knights of Anhedon’s host and the last battle of Aarthe. She passed the time, and she felt time passing her by. Her days were content, but they were also a routine she could not break away from. Her father, the Sisters, and the servants of the castle—none of them would let her vary the pace and rhythm of her life in the slightest, and no-one would say why this was so.

There had been a boy, not long after her sixteenth winter, who came to clean her chamber. He looked at her in a strange way, and she didn’t know what to make of it, until the day he tried to kiss her. She felt the hardness of his devil-bone against her. The Sisters seized him, and Milanda begged them not to hurt him.

She never saw him again. She asked her father about him, off and on, but he had nothing to say. Whispers reached Milanda’s ears: a skull smaller than the rest mounted on the spikes atop the bailey’s gate. But she was sure the whispers were false. Father could not be so cruel as that, surely. But she never left the castle, nor did she cross the outer yard to the bailey’s gate, so she did not know for certain.

And the boy’s face found its way into her dreams, where it spoke the language of maggots and worms. His eyes had been eaten by crows, and his skull was a nest for worse things. When she thought of him, she felt cold inside and the food she ate tasted like dead moths and ashes in her mouth. She tried not to think about him, but there was so little to do that she could not help but hear his voice, see his face, and think of his eyes. They had been kind eyes—before the crows took them.

“Why so morbid tonight, Milanda?” she asked herself, and went back to her reading.

*

Khale moved through the corridors of the castle, unseen. He only relaxed in the shelter of its richly tapestried rooms where he listened to the pounding of feet outside and the raw shouts of Leste Alen. This was all a distraction, really. It was something to do. He was ancient and would see Colm and Neprokhodymh come to dust in the fullness of time, and their people would expire too. The kingdoms of Barneth and Farness would fall as well.

Nothing lasts forever.

He would still be walking the earth when new empires arose, fell, and fractured into feuding city-states such as this once again. He might well undertake such a quest as this again. There was so much to be done in the world, but so much of it was the same as had been done before, countless times over.

Time was a straight river for many, and most of them drowned as they travelled its course, but for Khale, time was a very different thing; it was a cycle of living and re-living the same moments. It was a great wheel upon which he saw the world being broken again and again. These kings, queens, warlords and sorcerers who saw themselves as so unique were all much of a muchness: dismal creatures dressed in their costumes and masks. They were distractions also, and they would pass him by.

I am forever, he thought, these people are not.

They think themselves above me, and yet the day will come when I will crush their dust and bones be

neath my feet. All I have to do is wait. I do not need to raise my sword against them. They think life is a game of gold, adultery, and struggling for power.

It is not.

Life is but a game of bones, and everyone loses in the end.

He went out onto a balcony and looked over Colm as the first threads of dawn began to weave themselves through the horizon. He heard a voice—light and feminine—coming from not so far away. He turned to see a girl standing on an adjoining balcony. She was a fair enough creature. The light caught in the curled autumnal fall of her hair. Her figure was soft and slender beneath the rumpled looseness of her nightclothes.

He knew who she was: the Lady Milanda, Alosse’s daughter.

Leste came out onto the balcony to speak to her.

Khale saw Milanda’s eyes were sea-blue opals which, moments later, began to stream with crystal tears.

He returned to the shadows of the castle. Guards who were not dozing at their posts merely peered at him and wiped their eyes. He knew they saw him as little more than a passing flicker of the lamp-flames as he came to the iron door of Milanda’s bedchamber.

Well guarded and protected, Alosse, he thought. You have done well by her.

He listened at the door.

“I promise, your Grace. We will rout him out and slay him. Your father’s death will be avenged.”

He could hear how raw and wet was the voice of the Princess. “Thank you, my Lady of the Watch. I trust my heart and my father’s soul to you.”

“By your leave, your Grace.”

“Please, go. I will wait on word from you.”

“Aye, your Grace. We will have him before the sun finishes passing the horizon.”

Will you now, Khale thought.

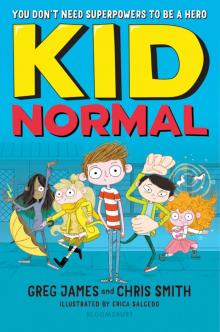

Kid Normal and the Final Five

Kid Normal and the Final Five The Sceptre of Storms

The Sceptre of Storms Made for the Dark

Made for the Dark The Sword of Sighs

The Sword of Sighs This Darkness Mine

This Darkness Mine The Door of Dreams

The Door of Dreams All Things True

All Things True The Stone of Sorrows

The Stone of Sorrows The Oeuvre

The Oeuvre Zombies by Moonlight

Zombies by Moonlight Lost Is The Night

Lost Is The Night Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1)

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One)

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes

Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes Kid Normal

Kid Normal