- Home

- Greg James

Made for the Dark Page 2

Made for the Dark Read online

Page 2

Rossiter breathed on his hands, hoping to warm them though he did not try to touch the performer and detect a pulse. Instead, he lifted the hood just enough to find the lips beneath. They were pale and without make-up; secretless yet not telling. They were masculine and feminine in perfect balance. He kissed those lips and felt a small, hot tongue flicker out and touch its wetness on his own. The moment ended and the performer’s hood fell back into place. Rossiter didn’t want to see the rest – there was no need. The show was over for him. He left the stage and gave a nod without a smile to the compère.

At the door to an upstairs room, he turned and looked back at the stage before leaving and saw what he’d expected to see. It was already empty, dusty, utterly vacant, and the tinfoil from the tattered stars was slowly coming away.

The Face in the Picture

Sometimes, it can be hard to be the person you are.

Though I suffered no trauma as a child; growing up I was possessed by the sense I was meant for lesser things than others. It was a feeling as much a part of me as my skin and bones – something I could not dislodge, no matter how determined I might be to do so. Such a natural foreboding about life led to my existing at a slight remove from the rest of the world – though I had one good friend who persisted for some years until I made a suitable end of things.

We worked together in administrative roles at the Royal Free Hospital in Belsize Park. It was a pleasant enough time and place in my memory; monotony is a comfort for me in the same way family and friends are for others.

After a few years together, my friend went on to better himself in various artistic spheres while I persisted in various familiar-yet-unfamiliar offices around London. I tried my hand at writing and self-published a few pamphlets of short poetry, which didn’t change my position in life at all. I still have a handful of stained, dog-eared copies somewhere on my shelves at home – Unwanted Things and Mice Thoughts; those were the titles and I’m sure you haven’t heard of them.

Among the things my good friend achieved after we stopped working in the same place was marriage to a beautiful woman. Her name was Angela and she was, as they say, something else; a true English rose. I envied him, even when his two daughters were born. His life, to me, seemed idyllic whereas my own was an interminable thing. My family was not composed of bad people but none of them cared much for me or I for them. Also, I was single then and I am single now – a condition one might describe as life-long, even terminal.

That all being said, my friend was kind to me and we met every three months to share a drink in his local pub – the Watergate – long after we stopped working together. One night, before I departed, he invited me over to dinner. The thought of spending an evening in the presence of Angela was enough to make me say yes though I didn’t tell my friend this. He might not have approved.

So, the day came around and I could not manage a jot of work until it was time to leave the office – I forget whereabouts I was employed during that period; Angel, perhaps. It is of no consequence to the narrative. I arrived at their home address at six o’clock sharp with a bottle of wine that I hoped was as reasonable as its price. I rang the doorbell and Angela was the one to answer.

“Are you well? You certainly look it. How long has it been?” she asked.

“Too long,” I said, in all honesty, and took her hand in mine – holding back the adolescent urge to kiss it like a chivalrous knight. She let me in, took my coat, and hung it up by the door. She showed me into the lounge where their two young daughters were curled up in the armchairs idly reading. The children were dressed for bed. I sat down on the sofa and rested my hands on my knees, making sure my fingers did not fret or pluck at one another like they usually do.

“Lesa, Ruthie, it’s time for bed. Grown-up time now,” Angela said to the girls in a light but firm voice. They looked up from their books, then looked at me. Lesa smiled. Ruthie regarded me carefully as if she knew me better. Could a child’s eyes espy the truth in so false a creature as myself?

“Come on now, both of you, bedtime.” Angela said – and they complied, leaving the room courteously. Lesa didn’t spare me a second glance but Ruthie looked me in the eye one more time. I was glad when the child was gone and out of sight. There were some parts of me I did not wish to be clearly seen, or understood; certainly not by someone so young and supposedly innocent.

Angela brought me a glass of fine sherry. “I’m afraid he’s running late as per usual. He works far too hard and far too long hours at that place,” she said.

“Yes,” I said, “but without his efforts. You wouldn’t have all this.”

I didn’t tell her how much I envied him; having the children, having her most of all, though I ached to. As admissions of undying love, one could hardly get more pathetic really. She interrupted my drifting thoughts, “Ah, here he is now.”

My friend arrived home without much ceremony, kissed Angela on the cheek, and then sat down to talk with me about this and that. We might as well have been in the pub. The details of our conversation don’t matter now, and they never did at the time, because I kept on watching for his wife who had disappeared through a door as soon as he began to speak. Angela had my sole attention even when she was not present – she held me rapt though she did not know it at all. I listened to her light step as she climbed the stairs, no doubt to kiss the children goodnight like the perfect mother she was – so unlike my own.

“You all right there?” my friend asked and I came back to myself, having drifted off again.

“Yes, yes, quite all right. Sorry, I was lost there for a moment.” I made my excuses to divert possible suspicion; not that there was any reason for it – watching and listening were hardly crimes. Angela returned and we went through to the dining room for dinner. I can’t remember what it was we had but I am sure it was splendid. She was an excellent cook among her many talents. But whatever I ate was nothing compared to merely being near her for the span of an evening. The idea of returning to my grubby hovel of a flat began to weigh on me even at that early point in the proceedings.

There was laughter between us but mine was empty. There were smiles shared but mine was hollow; a mask to entice and deceive. I remember my face hurting from the laughter and the smile. I remember resenting them both for it; reminding me of my discomfort in enforced social discourse.

Afterwards, we were sitting around the dining table nibbling on after-dinner mints and sipping fragrant black tea when my friend said, “Let’s have a photograph together. We’ve known each other for simply years and we still don’t have a single picture of the three of us. We must remedy that.”

“A wonderful idea,” Angela said, “wonderful.”

I’m sure I concurred though not without self-consciously touching my face and hair; neither being aspects of myself I was very proud of. My skin being too sallow and my hair too thin and wispy. That said, the evening had been a good one and a memento of a sort would be nice. A picture of myself and Angela – perhaps I could cut my friend out of it somehow with the clever use of scissors.

My friend produced a camera, set it up and set the timer so that we had about ten seconds to arrange ourselves. Angela and I sat side by side whilst my fried positioned himself behind us, a warm hand resting on either shoulder; a reminder of our friendship and my position in it. Flash – the photo was made. He said that he would post me a copy once he’d had the film developed. It shouldn’t take too long as they had a family holiday coming up: a weekend in the Cotswolds, away from it all. I thought of my holidays spent in the shabby bed-and-breakfasts of the south-east coast – and I won’t set down just how black and miserable were the feelings that came rising to just below the surface.

There’s not much more to say of the evening – except that I left closer to midnight than I intended and with a stumble in my step as I weaved my way to the bus stop.

I think I might’ve cried myself to sleep that night in my cold, damp bed but it could have been a dream. I have a lo

t of those.

The photograph arrived in the post the following week. I set the plain manila envelope it came in against the salt and pepper pots on my small, square kitchen table. There was no room in my abode for a dining room so I ate at this scuffed and chipped formica surface with the wood-chip painted wall staring back at me from the other side. Today, I stared at the envelope as I gnawed upon and slowly swallowed my scrambled eggs and toast. I left it there, went to work, and when I returned home then I opened it.

The photograph? I regarded it. No, I didn’t look at it – I regarded it for what felt like an hour but was probably only a few lonely minutes. There was my friend, his wife, and then there was the pale creature intruding into their intimate space; violating it. I looked at me and something that might have been a smile but wasn’t crept across my lips. I set the photograph down and picked up a greasy penny that’d been resting on the kitchen windowsill for god knows how long. I sat down, turning the dirty coin over in my fingers as I thought and thought upon what I was about to do. With thumb and forefinger, I kept the photograph steady against the kitchen table as I set to work.

I can barely describe how it felt; each stroke of the coin, the feeling of friction produced by its coarse edge, and the sight of Angela’s countenance, bit by bit, little by little, being scratched away. My breath was catching in my throat. My teeth were set against each other; too tight to grind or click. I could feel a trembling go through me that turned my stomach and set my knees to shaking. I was being overtaken by pure abjective impulse – and then I stopped. She was gone; Angela’s face was no longer there. An uneven, scored, crude oval of whiteness was all that was left. I looked at it. I put it away somewhere; a drawer, I think. Face-down. I tried to forget about what I’d done.

Just over three months passed and it was about time for the usual meeting with my friend at the Watergate. I telephoned and asked when would be a good evening for us to meet. He sounded strange as he spoke, “I’m sorry, Katherine. Now’s not a good time. I’m not sure when will be a good time. Not for a while.”

“Oh, really?” I asked.

I could hear sounds in the background; children crying, and something else – other sounds like someone trying to speak who could not. They were very sad sounds to hear; echoes almost.

“I’m very sorry,” he said, “Angela’s … very unwell and I don’t know what to do about it. I will have to let you know when will be a good time, if ever.”

And that was it. He hung up – didn’t even wait for me to say goodbye. He didn’t ask me to come around or to help out in any way. And I didn’t call him again; not after another three months had passed, not after six. There had been something in his tone on that last call – an understanding. How he came by it I think I’ll never know though I myself remain not entirely clear what had transpired. I knew only it had happened and that was the sum of it. A few years later, I read about his suicide in the local paper; a small item just before the sports pages. Survived by his wife and children, it said. There were no photographs.

Afterwards, my life didn’t change much and nothing really happened to me. I am now as I was then; working in various offices, growing much older, more sallow in the face, and losing my hair as my mother did before me. I look more and more like her every day according to some. There are times though when I think of my friend, his wife, and their children, and when I do – well, I smile.

Tangerine Dream

or

A Curious Evening in the company of Kafu Nagai

I awoke in a Japanese house. The cream fusama rippling slightly from a tangerine-scented breeze. I didn’t know how I came to be there. I had never been out of my home country, my home town, yet here I was in a foreign place in a foreign land. Getting to my feet, I examined myself for signs of violence or kidnap. I found none. My body was dressed in a plain kimono that reached down past my knees. A pair of slippers, soft and silk-lined, were by the partition door. I slipped them on and rested my hand on the wooden frame, feeling it tremble from whatever weather was disturbing the structure of the house.

I stood there for an inestimable time with my eyes closed; just listening, just feeling. The quiet was near-absolute. The lowing of the wind outside reached my ears, nothing else did. I was alone in this strange house. I should have been scared but I was not. It was strangely comforting to be alone in a place I did not know. To be out of my old life, the one that had wound tight about me like the ageing skin of a snake.

People often speak of making a new start. Starting afresh. Starting over. Of course, such a decision does not usually lead to a nocturnal dislocation such as this. Still, it did lead me to wonder whether such a thing was possible. Could the unconscious, worn to the quick by routine, desperate for difference, for change, for otherness, act upon the person and transport it elsewhere. Literally take it into a new life, to begin afresh, to start over. There were no mirrors in the room so I could not check and see if my face was at all different. Being in Japan, I imagined it would have to be. I wondered whether this dislocation had landed me in the present, future or the past. All the possibilities intrigued me. It had been a long time since I last experienced possibility as a part of my life.

I opened the shōji and stepped through into the rōka. It was lit by small kerosene lamps that were set along the floor at intervals of five feet or so. The glow cast by the lamps was autumnal; soothing to my senses, making me walk slowly, a somnambulant abroad. The shadow cast upon the wall was from one of the lamps, that was my first thought on it. Then, I examined it more closely and realised it was not. The design of the lamps being hunched and squat, I thought the silhouette cast to be a simple deformation caused by shape, texture and obstructive surfaces.

Then, of course, I knew the shadow was cast by a man and that man was my host.

I was ambivalent about meeting him.

Why?

Because he must have brought me here and no-one who brings one to a place without their consent means them good. Not that good is much of a concept, really. Perhaps I should say that such a person usually desires to disrupt one’s schedule. Mess up the routine. Break the simple securities of the plain, ordered world down for no other reason than to do so. No, I did not want to meet such a person.

That all being said, and thought, my sense of objection was rendered moot. The man who owned the shadow opened the shōji while I dithered on the spot, caught up in my usual web of worried reflection and ambiguous, uneasy, over-paused response.

I did and did not recognise him. I had not known him in life but his face was familiar to me in this underlit limbo. A long, louche face with large ears. The mouth down-turned in a melancholy mode. The eyes staring out at me from behind circular black-rimmed glasses. He was not dressed as I was. He wore a grey suit like so many I had seen worn by tired businessmen rocking half-asleep on the trains and buses in my home town in my home country.

“Who are you?” I asked, already knowing.

“I am Kafu Nagai and you are late for the end of the world.”

*

We sat opposite one another, waiting for the green tea he was brewing to steep. His eyes were intent on the pot, not on me. I was wondering what was going on. I had questions for him. None I dared ask. I was sitting here with a man dead. Gone fifty years ago. He was brewing tea. How could any of this be happening?

It was very strange, too strange. Consorting with the dead was a pastime for the mad and the elderly. I am neither. My life is a wonderfully contained thing. My movements from morning to night could be used to set clocks by. I have read a few books that have mentioned this man but I am no great admirer of him, or his work. Why has he come to me now, or I to him? This just should not be.

“The tea is ready.” He said.

We sat and drank and we talked and, at some point, I clumsily burned my hand on the teapot. There was much to talk about with the world at an end. Words, thoughts, feelings, sights, smells; all of these things were soon to cease and come to an end. Just like

that. What then of them. What did they mean. What was their purpose. People wailing, screaming and praying to gods and killing their fellows on the say-so of said deities. An atheist who hears voices is assumed mad but a theist who hears voices is assumed blessed. Of course, there are the other religions; civil rights, individual rights, patriotism, the worship of the commercial. The love of disco lighting over the amber twilight. The wabi-sabi dwelling in the shadows of concrete-building husks. The natural whisper of yuugen from a weeping willow tree, its limp leaves swimming in the night’s vapours. Oh, so much we talked about that was little, large and nothing at all.

Something was to become nothing. The little things in life were to be no better or worse off than the supposed greater. What to do, where to go, how to be. There would be no more of it. How beautiful it was.

For some reason, a reason many would loathe me for, this made me smile. It was a smile best suited for the funeral of a bitter foe though said foe would have to have been a much-loved part of one’s life to begin with. Yes, there was a melancholy to the expression, a pulling of muscles that did not want to be pulled, a tightness that comes when old wounds are scratched at it, made to give up their blackly-seeded bile. That all said, the sweetness of release too, of a thorn taken out and cast far away.

“Would you like to see it?” asked Kafu Nagai, “the end.”

I nodded my gracious thanks. He leaned to his feet with a cry and a crack of old bones. Shuffling along, he went to the outer wall and slid open an outer shōji, just a little. “It is all coming apart you see.” he said, “Like a bunjinga, is it not? Painted by hands inspired by another place, another time. Maybe there is some namban in it too, eh? Who would think that, when it all came to an end, we would see the world as a thing so foreign, poisonous, and exotic to ourselves?”

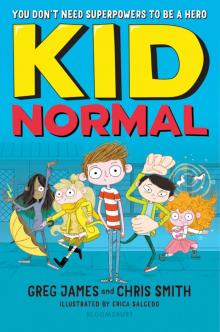

Kid Normal and the Final Five

Kid Normal and the Final Five The Sceptre of Storms

The Sceptre of Storms Made for the Dark

Made for the Dark The Sword of Sighs

The Sword of Sighs This Darkness Mine

This Darkness Mine The Door of Dreams

The Door of Dreams All Things True

All Things True The Stone of Sorrows

The Stone of Sorrows The Oeuvre

The Oeuvre Zombies by Moonlight

Zombies by Moonlight Lost Is The Night

Lost Is The Night Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1)

Under A Colder Sun (Khale the Wanderer Book 1) The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One)

The Sword of Sighs (The Age of the Flame: Book One) Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes

Kid Normal and the Rogue Heroes Kid Normal

Kid Normal